Few lives are exempt from moments of defeat and disappointment. All too frequently, those moments attract comments which, although well intended, usually make the situation worse. Just one example is telling someone dealing with romantic rejection that "It's better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all." No matter how well meant, the sentiment gives little comfort or consolation. The baseball equivalent is when after a heart-breaking loss, someone says "It's only a game." Not only doesn't it help, there is the implication that games aren't important. But that contradicts the very definition of a game as "a contest played to a definite result" - why play if the result doesn't matter? There does, of course, have to be some perspective. The importance of games is relative - no vintage baseball game, for example, has any lasting significance, no matter how important it may have seemed at the time.

Some games, however, are of great importance simply because of what's at stake. Major league games that help decide pennants, playoffs and World Series are obviously at the top of the list. When such games combine dramatic moments with record setting performances and controversy, they live on, not just in the memories of contemporary witnesses, but in baseball history. Such games are rare, but there is even a more exclusive category within that already small group - games that have meaning beyond baseball itself. One such game was played 75 years ago today at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn - the fourth game of the 1947 World Series between the New York Yankees and the Brooklyn Dodgers.

As baseball's biggest stage, the World Series is where the game's greatest stars are expected to shine the brightest. One of the most interesting things about this 1947 game, however, is the stars were largely on the periphery while the supporting cast took centerstage. On that warm October afternoon, a player well past his prime, a pitcher with a losing record and a fill-in manager combined to give baseball one of its greatest games. While all played their part, none of it would have happened without Bill Bevens, the Yankees starting pitcher. John Drebinger of the New York Times, one of baseball's most respected writers, called Bevens "good without being lucky." Although the Yankee pitcher's had indeed suffered past misfortunes, such as eight, one run losses losses the prior season, this day would give new meaning to being unlucky.

Bevens had a losing record in 1947, but in this game, the Dodgers were helpless against his dominating repertoire of pitches, all working at maximum effectiveness. Bevens' fastball and slider were "hopping like electrified atoms," while his curve was "breaking as if someone was snapping it off." Jackie Robinson even claimed Bevens was throwing a pitch he (Robinson) had never seen before. But in a bizarre twist of fate, worthy of Greek mythology, the gift of unhittable pitches came with the curse of being unable to control where they were going. The result was equally bizarre. Over the first eight innings Bevens held Brooklyn hitless, but walked eight, one of whom came around to score.

Had the Dodgers pitchers been as ineffective as they were in the first three games of the series, the only question, as the game headed to the ninth, would have been whether or not Bevens would pitch the first World Series no-hitter. But an unlikely supporting player made sure much more was at stake. At a loss for a starter for game four, Dodger manager Burt Shotton gambled on the injured Harry Taylor. It proved to be a bad wager, since Taylor lasted only four batters, leaving the bases loaded with none out and one Yankee run across the plate. With few options left, Shotton called on Hal Gregg and his 5.87 ERA. Amazingly Gregg was more than equal to the task. Not only did he escape the first inning without any additional damage, Gregg allowed only one additional run and after eight innings, the Yankees held a slim 2-1 lead.

After Gregg departed for a pinch hitter, his replacement, Hank Behrman got into trouble in the ninth when the Yankees loaded the bases with only one out. With the ever dangerous Tommy Henrich coming up, Shotton brought in Hugh Casey, his top reliever. The matchup was a repeat of the fourth game of the 1941 World Series, probably the worst Dodger moment at Ebbets Field. On that day, Casey struck out Henrich for what should have been the final out in a Dodger victory. But, as no Brooklyn fan will ever forget, Dodger catcher Mickey Owen couldn't come up with the ball and the Yankees rallied to win. Certainly neither Casey or Henrich had forgotten even though they showed no emotion as they took their places. Casey threw a low curve that he later described as "a perfect pitch." "Old Reliable" hit it right back to Casey for an inning ending double play and just like that, on one pitch, the Yankee threat was over.

If Bevens was going to make baseball history, not to mention help his team take command of the series, he had to make the 2-1 lead standup. The Yankee hurler walked to the mound "full of sweat and hope." Both were understandable, especially the former, since Bevens had already thrown over 120 pitches. As he completed his warmup pitches, radio broadcaster, Red Barber felt an "almost breathless hush" throughout Ebbets Field. If so, it didn't last long. As Bruce Edwards stepped to the plate, "a might roar swept over the entire stands" and then "echoed over Bedford Avenue as if to the tell the world that a great event was taking place."

Although Edwards had struck out three straight times, the Dodger catcher hit a line drive that appeared "certain to hit the [left field] fence." The blow brought a "mighty cheer" from the Dodger faithful, but Johnny Lindell made a "stretching grab" for the first out. Next up was center fielder Carl Furillo, in the game only because Pete Reiser was injured. Furillo took a strike, but Bevens again lost the plate throwing four straight balls for a record tying ninth walk. Still needing two outs, Bevens faced Spider Jorgenson. The Dodger third baseman swung at a 1-1 pitch and "fouled meekly" to first baseman George McQuinn. The blow may have appeared "meek" to the writers in the press box, but it didn't lessen the pressure on the field. According to Dick Young of the Daily News, McQuinn "was as white as a sheet as he made the catch."

It was now "the 59th minute of the 11th hour" for the Dodgers. Brooklyn manager Burt Shotton had few options, but he wasn't about to give up. That Shotton was even in this position would have been hard to believe during spring training. Just as the Dodgers were about to make Jackie Robinson a Brooklyn Dodger and take on baseball's long history of racism, manager Leo Durocher was suspended for the entire season for unrelated matters. Shotton, whose prior managerial record was below .500, had only two things going for him - he was available and Dodger General Manager Branch Rickey trusted him. The trust was rewarded with a National League pennant with Robinson playing a key role. Shotton had a reputation of not being "afraid to make decisions" which was good because the situation called for aggressive measures. Somehow a team that didn't have a hit all day, had to move the tying run from first to home.

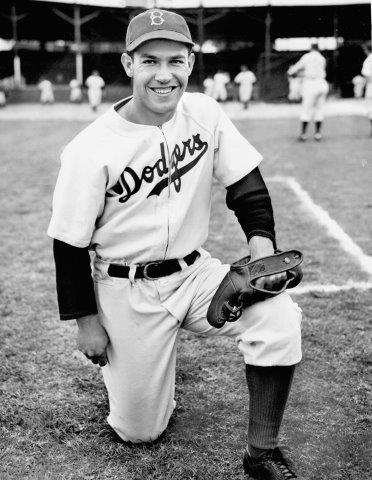

Trying to improve his team's chances, Shotton made two substitutions, first sending Al Gionfriddo to run for Furillo. If there was ever a bit player on the Ebbets Field stage that day it was Gionfriddo. He came from Pittsburgh in June as a throw-in in a trade that sent Kirby Higbee and four other Dodgers to the Pirates for $100,000. Writers cynically labeled Gionfriddo "satchel boy" because supposedly his only role in the trade was to carry the money from Pittsburgh to Brooklyn. Although some writers predicted he would be quickly sent to the minors, Shotton "valued" Gionfriddo, especially for his speed, and kept him for "special assignments." If there was ever a "special" moment this was it, but the move was still surprising since it was only the second time all season Gionfriddo had been called on to pinch run.

If Shotton's first substitution was surprising, his second move, sending Pete Reiser to pinch hit for Casey, suggested the Dodger manager was in denial. Although Reiser hit .309 in 1947, the star-crossed Dodger had what was thought to be a badly sprained right ankle. In fact, he had broken a bone in the ankle. Reiser couldn't even stand on the foot during batting practice so he retreated to the locker room to soak it. After returning to sit on the bench for the first three innings, he went back to the locker room, took off his uniform and soaked the ankle again. At this point Doc Wendler, the Dodger trainer, told him not to bother putting his uniform back on since he clearly couldn't play. Unwilling to surrender to the pain, Reiser dressed and was back on the bench even though his ankle was reportedly the size of "a cantaloupe."

Exactly what Shotton said to Reiser isn't clear, but Shotton knew his star player always responded to a challenge and he somehow goaded Reiser into volunteering to pinch hit. As the injured Brooklyn slugger went up to the plate, the noise was so loud, it was impossible to hear him announced as a pinch hitter. After taking ball one, Reiser fouled off Bevens' second offering with a "terrific lunge [that] brought him down to his knees." The effort was so painful "you could read the torture on [Reiser's] face." Unable to take advantage, Bevens threw ball two.

With Reiser ahead 2-1 in the count, Shotton decided it was time to risk everything on one throw of the dice or rather on Gionfriddo's legs. The Brooklyn manager gave the steal sign - the first of two of the most controversial managerial decisions in World Series history, both in the same inning. Whatever the Brooklyn manager was thinking, his decision wasn't based on past performance since Gionfriddo had been thrown out on three of his five steal attempts during the season. Standing near first, Gionfriddo was more than a little surprised. Years later, he claimed "I couldn't believe my eyes. If I get thrown out the game's over" which would give Bevens his no-hitter and Yankees command of the series.

Equally surprised, the crowd let out "a feverous screech" as Gionfriddo took off. To make this "special assignment" even more difficult, Gionfriddo "slipped on the first step" and was sure he "was a dead duck" destined for World Series infamy. Shotton, however, was counting/hoping that Yankee catcher Yogi Berra would continue his poor throwing and sure enough, the future Hall of Famer's throw was high. Shortstop Phil Rizzuto grabbed the ball and tagged Gionfriddo who slid head first trying to compensate for the bad start. "For the briefest moment, all mouths snapped shut and all eyes stared at umpire Babe Pinelli. Down went the umpire's palms" and Gionfriddo, not to mention the Dodgers, were still alive. Rizzuto who was jumping "around like he had an electric shock," clearly disagreed. No one was more relieved than Gionfriddo who claimed "any kind of throw would have had me." Shotton, when asked later why he made a move which, if it failed, would have earned him a special place in Brooklyn baseball hell, simply said "I wanted him on second."

Reiser now had a hitter's 3-1 count, leaving Yankee manger Bucky Harris with three choices. He could walk Reiser, knowing the Dodgers had no more left handed batters and that Eddie Stanky, the next hitter, had little power. The second option was to replace Bevens with Joe Page, the Yankees star reliever who had warmed up earlier in the game. With Bevens flirting with baseball history however, it was unthinkable to make that move. Finally Harris could have had Bevens pitch to the obviously limited Reiser. But that meant throwing the ball over the plate since anything out of the strike zone would walk Reiser anyway. While the Brooklyn slugger was hampered by his right ankle, the other foot which he hit off was sound and ready to take advantage should Bevens groove one. Harris never hesitated. He ordered Bevens to put Reiser on first for the inning's second controversial decision. In doing so, Harris violated baseball's unwritten rule of never putting the winning run on base and, as Dick Young observed, made himself "an eternal second guess target." The walk was Bevens 10th setting a World Series record of dubious distinction.

Somehow Shotton had parlayed a seldom used bench warmer and a crippled slugger into managerial moves that put the tying and winning runs on base. No sooner had Reiser limped to first than he was replaced by pinch runner Eddie Miksis. By walking Reiser, Harris probably thought he was choosing to pitch to leadoff batter Eddie Stanky since Shotton had only pinch hit for Stanky once all year. Although Stanky was no power hitter, he also wasn't an automatic out and had already broken up one no-hitter that season. If Harris was surprised when Stanky was called back to the dugout, he wasn't the only one. Upon hearing Shotton call his name, Cookie Lavagetto thought he was running for Reiser and had to be told twice he was pinch hitting for Stanky.

If it had been up to Dodger General Manager Branch Rickey, Lavagetto wouldn't even have been in the Brooklyn dugout. Although he was a four time all-star, Rickey didn't believe Lavagetto, at 35, had much left to offer as a player. Before the season, Rickey tried to convince Lavagetto to retire and become a manager in the Dodger farm system, but the veteran player believed he could still contribute. The results were mixed, "the last of the [Dodger] old guard" hit just .261 in 69 at bats and was only slightly better as a pinch hitter. The "swarthy complexioned veteran" did have a key pinch hit in a September game against the Cardinals, but was 0-10 since then including an unsuccessful pinch hit attempt in the first game of the series.

Lavagetto entered a scene that was "beyond the final reach of any imagination." "Women fans nervously patted their hair" while their male counterparts "clasped and unclasped their hands." In the press box, even "the blasé sportswriters . . . sat on the edge of their chairs waiting to see something they [nor anyone else] had ever seen before." The noise was so loud the crowd mike in the radio booth was turned off and Red Barber was told to get as close as possible to the microphone. Keeping with the Yankees scouting report that Lavagetto had trouble with "hard stuff away," Bevens' first pitch was "slightly high and towards the outside." Making the scouting report look good, Cookie "swung lustily" and "missed . . . by a full foot." Lavagetto would later claim his problem was with inside pitches, not outside ones.

Now only two strikes away from baseball immortality, Bevens threw the second pitch in the same place, "harder if possible." Lavagetto swung and drove the ball "on a low whistling line" toward the right field corner. Since Lavagetto was more of a pull hitter, Yankee right fielder Tommy Henrich was positioned towards center field. Before the game, "Old Reliable" had practiced for just such a moment, fielding balls hit off the fabled right field wall for 15 minutes. As he watched the play develop from the dugout, Dodger veteran right fielder Dixie Walker thought Henrich had two choices. He could gamble on jumping for the ball or he could play it off the wall. If Henrich gambled and missed, not only the no-hitter, but the game was lost. Playing it off the wall meant losing the no-hitter and conceding the tying run, but gave the Yankees a chance to win the game.

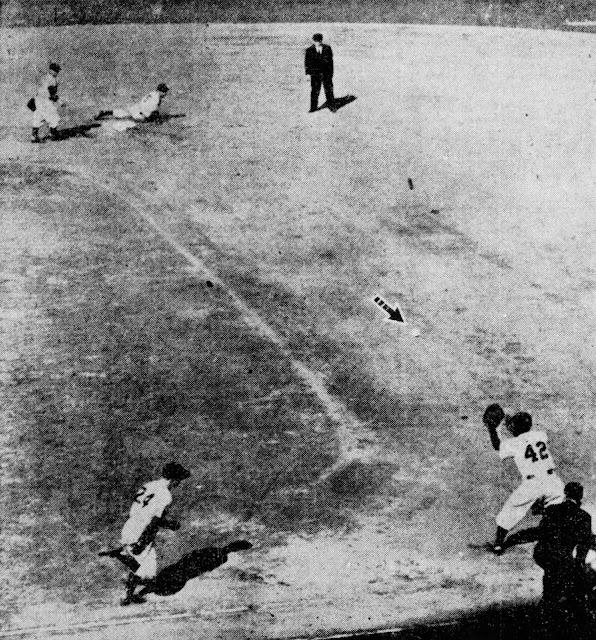

Considering the Yankee outfield had already saved Bevens and the Yankees with three difficult catches, long-suffering Dodger fans could have been excused for expecting another heart-breaking late inning near miss. As "reliable" as Henrich was, however, he couldn't catch a ball that hit the wall six to ten feet over his head. While the Yankee right fielder tried to pick it up, Gionfriddo rounded third and scored the tying run. It took Henrich two tries to come up with the ball and throw it to McQuinn at the edge of the outfield. The Yankees first baseman "whirled desperately and heaved home," but as he threw, Miksis was sliding, unnecessarily, across home plate with the winning run.

Suddenly, at 3:51, "God's little acre became bedlam." "For a moment everyone on the field seemed stunned," then the "whole Dodger bench was out on the field, capering madly, and hugged Gionfriddo and Miksis and all but tore Lavagetto's uniform off." Lavagetto, baseball's newest legend, "fought his way down the dugout steps - laughing and crying at the same time in the first stages of joyous hysteria." At the other end of the emotional spectrum, the "Yankees walked off the field unnoticed." "The least noticed of all was Bevens, who for a few moments before, had been a step away from everlasting baseball fame," but "was now just another good guy who failed to win." Remembering Bevens history of bad luck, Arthur Daley of the New York Times thought fate had played the "shabbiest trick of all" on the unfortunate pitcher.

Silence reigned in the press box. "Not a telegraph instrument ticked, not a typewriter sounded. For once the press was speechless." After a few moments, the scribes began struggling for words to describe what almost defied description. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle tried superlatives such as "hectic, amazing, record-setting, [and] magnificent," before leaving it to readers "to supply the rest of the adjectives." Recognizing the game would live in history, Stan Baumgartner of the Philadelphia Inquirer predicted that "the grim minutes leading up to the finale in which Brooklyn suddenly turned apparent defeat into an incredible victory will never be forgotten by the fans who experienced them." Some still couldn't quite believe it, Arthur Daley wrote that the "more you think about it, the more you wonder if it was just an optical illusion." Capturing the extreme emotional swing generated by just one pitch, Martin J. Haley of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat called the ending "the most spectacularly dramatic finish that ever gladdened the hearts of one baseball side and broke those of the other contingent."

Needless to say there was no shortage of post-game commentary. Grantland Rice, one of the leading sportswriters of the day, pointed out Shotton's "indefinable, second, third, or fourth sense" in sending Lavagetto up to pinch hit. Chester Smith in the Pittsburgh Press called the move "one of the most successful stabs in the dark any manager ever made." Queried about the move, the Brooklyn manager matched his terse explanation of the decision to send Gionfriddo by asking rhetorically who would have been a better choice. Over in the Yankee locker room, Bevens manfully took full responsibility. He said the pitch was exactly where he wanted it, the loss was due to his lack of control and losing the game was more disappointing than missing out on the no-hitter.

Fortunately for Bevens, he got another chance and redeemed himself by pitching two and two-thirds innings of scoreless relief in the Yankees seventh game victory. Also far from finished were Gionfriddo and Lavagetto. In the sixth game, "satchel boy's" dramatic catch robbed DiMaggio of an extra base hit and helped insure there was a seventh game. The day after his ninth inning heroics, Lavagetto, in almost exactly the same situation, had another chance, but this time, he struck out. However, the following day, in game six, he drove in the tying run to help the Dodgers tie the series.

"It was only a game. But was it? It was America - and all that America means wrapped up and expressed in one single pitch, one single hit."

We'll never understand what Baumgartner meant by America, but we do know what he witnessed that historic day at Ebbets Field. To begin with, two Dodger pitchers, Hal Gregg and Hugh Casey overcame past failures to help their team. Gregg had been ineffective all season, but when his team needed him most, he stepped up and kept the Dodgers in the game. Inserted into a very tight spot at a crucial moment, Casey used his 1941 failure as motivation to turn back the Yankee threat and, at the same time, earn redemption. Even more impressive is Burt Shotton, who had little, if any, experience in managing in big games. Yet he refused to give up, even when all he had left to work with was two border line players and a crippled star. Instead of bemoaning what they didn't have, Shotton focused on what the three had in abundance - speed, courage and experience. Al Gionfriddo, Pete Reiser and Cookie Lavagetto not only rewarded their manager's faith, they used those qualities to win not just any game, but one on baseball's biggest stage.

Credit is also due to Bill Bevens, even though he wasn't successful. Throwing 138 pitches over the course of that long afternoon, the Yankee righthander struggled with what may be the most difficult challenge any pitcher ever faced - pitch winning World Series baseball with great stuff that he couldn't control. For almost nine innings Bevens did just that and when, in the end, he failed, he not only took responsibility, but was more concerned about the team losing than his own personal disappointment. And at the time, he had no idea he would get a chance to redeem himself. On that long ago day in Brooklyn, these seven men exemplified some of the best human qualities imaginable - overcoming past failures, rising to the occasion, never giving up, doing what they could to help their team and, when necessary, losing with honor. Those virtues aren't exclusively American, but they characterize our country at its best. There are few better examples than this memorable day in Brooklyn, seventy-five years ago today, in what was unquestionably not "only a game."

Fantastic essay John. Your narrative on this inning + photos and diagrams would make a great Youtube video

ReplyDeleteJoe, Thanks very much. I've been thinking about creating a Power Point presentation, but a video is an intriguing idea that I'll check out. I'm also wondering whether this is a book here as there are a lot of story lines and depth to the included story lines that didn't fit in a blog post.

Delete