On Tuesday, October 23, 1855, a baseball game was played at the foot of Chestnut Street in Newark, not far from today's Penn Station. While the Newark Daily Mercury called the field one of the teams' home field, it was likely little more than a vacant lot (and apparently remains so today). With two innings in the books, the St. John's Club held a 10-2 lead over the Union Club, but it began to rain, ending the day's play. Since both sides were likely playing mostly for fun, the losing Union Club was probably just as disappointed as the winning St. John's team. According to the Mercury, the game was to replayed that Friday at the same ground which was the St. John's Club's home field. No report of the rescheduled game or any other mention of the two teams has been found so we know very little about them and are not likely to find anything more. In most cases, the game and the teams would be forgotten, were it not for one word in the four sentence article - the insensitive nineteenth century adjective "colored," where today we would say African-American or black. That one word, however, makes this an historic event because, as of this writing, it is the earliest known instance of African-Americans organizing to play baseball anywhere in the United States.

Many years later, baseball could still be played at the foot of Chestnut Street (center-right)

The only thing that can be said with any certainty about these two clubs is that the St. John's Club was a Newark team since the field at the "foot of Chestnut Street" was definitely a Newark baseball field. 1855 was the year organized baseball first took hold in New Jersey and it is not surprising that as the state's largest city, Newark had the most teams - at least four other teams can be documented. For one of the clubs to come out of the local black community, however, is no small matter, if for no other reason because of the very limited pool of potential players. According to the 1855 New Jersey state census there were almost 9,800 white males over the age of 16 in Newark and they formed four baseball clubs. Newark's black male population was a minuscule 557 and they formed at least one and possibly two teams the very same year as their white counterparts, raising the question of how Newark's small black community learned about this "new" game so quickly?

Black Barbershop - Richmond, Virginia - The Illustrated London News - March 9, 1861

Historians Peter Morris and Richard Hershberger have written that at the beginning of baseball's first significant growth period (1855-1860), the game spread primarily through direct personal contact. Either you had played baseball yourself, watched it being played or spoke to someone who had either played or watched. It seems like those opportunities would have been limited for such a small minority living mostly on the margins of society. A look at an 1855 Newark Directory however offers some possibilities. A total of 167 black men are listed in the directory, most likely those who had a permanent address. While the leading occupation was laborer, second was barber and the 13 black barbers certainly didn't make their livings cutting the hair of the other 500 or so black men in Newark. Rather they catered to a largely white clientele, young white men who were likely to talk about this new game while being served or waiting for service. There is also the intriguing possibility of the O'Fake brothers, Peter (barber and musician) and John (music teacher). The two men were part of the city's small black middle class with Peter having an 1860 net worth of $5,000. The two men led a band that later played at the annual dances of the Newark Club - the city's first baseball club.

Newark's black community's achievement of starting a baseball club the same year as their white counterparts is even more impressive when considered in the context of the state's racial history, a story that is far too little known. It is perhaps best symbolized by a business transaction described in James J. Gigantino's The Ragged Road to Abolition, Slavery and Freedom in New Jersey, 1775-1865. In February of 1856, just a few months after the St. John's-Union game, John Hagaman of Raritan New Jersey sold some of his property to Charles Sutpin of Somerville probably as part of a planned move to Illinois. The property, however, was not livestock or real estate, but Catharine a 67 year old "slave for life," an act that may surprise us today on several levels. Some may be surprised to know there had been slavery in New Jersey while others more familiar with the story may be shocked to learn slavery still existed in the state more than 50 years after it had been abolished. The reason for this seeming contradiction is New Jersey eliminated slavery in a way that insured the path to black freedom would be long and arduous.

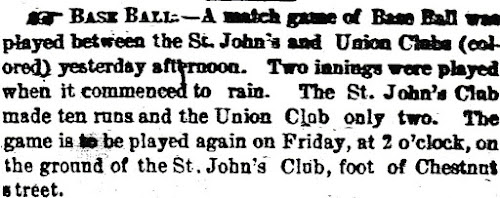

Newark Daily Mercury - October 24, 1855

Slavery in New Jersey began in colonial times and by 1800 there were over 12,000 slaves in the state with some of the largest concentrations in Bergen (2,825) and Essex Counties (1521). It was not until February of 1804 that the state legislature passed a law abolishing slavery in New Jersey but without freeing a single slave. Anyone who was a slave at the time (like Catharine) remained a slave for life. Only those born after July 4, 1804 were emancipated and not until their 25th (males) or 21st (females) birthdays. One of the many negative by-products of gradual emancipation was limiting, if not preventing, the growth of free black communities in New Jersey. It was not until the 1830s that there was a critical mass of free blacks who could and did begin forming their own institutions including schools, churches and even baseball clubs. Seen in this larger context, the 1855 baseball game takes on added significance as one more way the black community showed that in spite of white stereotypes, they were just as competent and capable. It may have been a small thing, but small things matter especially in fighting prejudice. Baseball may be just a game, but on October 23, 1855, those unidentified, but no less important, young black men showed it can be a lot more.

No comments:

Post a Comment