Considering the strict limitations society played on women in the nineteenth century, it is no surprise the idea of women playing baseball found little if any favor. If that was not bad enough, there was an added barrier because baseball first had to be justified as a suitable activity for adult males. Early baseball promoters had to convince the public that baseball was no longer just a boy's game, but an appropriate activity for grown-up men. It was necessary, therefore to stress the game's manly nature, and if baseball was manly, how could it be a game for women? Yet, as we might expect, discouraging women from playing baseball was far easier than prohibiting them from doing so. I've written before in this blog about early women's baseball in New Jersey and will cover some of the same ground in my forthcoming book, A Cradle of the National Pastime. However, that book stops in1880 while the upcoming Morven exhibit on New Jersey baseball will go through 1915 allowing for further coverage of that part of the story. In trying to understand women's baseball throughout this era, I owe a major debt, as do all baseball historians, to Debra Shattuck and her groundbreaking book, Bloomer Girls: Women Baseball Pioneers, a work, I wholeheartedly recommend to anyone interested in baseball history.

Trenton Evening Times - October 12, 1883

Dollar Weekly News (Bridgeton, New Jersey) - July 28, 1883

1894 Bloomfield baseball club - a year earlier four of those pictured here participated in the game with the female Cincinnati Red Stockings

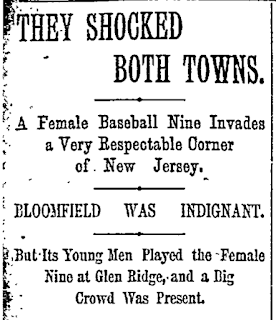

Naturally, the mothers of the Bloomfield players were infuriated and demanded their sons withdraw from the game. Surprisingly, however, in this case, the young men refused to obey their mothers, and probably their fathers as well, and the game went on. Although "the good people [of Bloomfield and Glen Ridge] vowed that nobody who went to the show could have further title to respectability," some 1,000 people reportedly attended, about 600-700 paying the 25 cent admission charge with the rest watching from a nearby hill. "The surprise of the day," however was the presence of "at least fifty young ladies of undoubted respectability," who were "accompanied by escorts in smart raiment." For shame, indeed! Nor was this the end of the scandalous behavior as "half a dozen fashionable carriages with coachmen" watched the game from their coaches without paying admission. Although the Red Stockings had some of the country's best woman players, including Lizzie Arlington and Maud Nelson, the Bloomfield boys prevailed. But in a very manly gesture, they gave the visitors 80% of the gate receipts.

New York Herald - May 7, 1893

Unfortunately for the mothers and other disapproving people in Bloomfield, word of the game spread far and wide, to the point the New York Herald, one of the country's leading newspapers sent a reporter to cover it. That coverage, in turn, insured not just national, but international attention, including an article in a London newspaper which found the behavior of the players did not meet the highest standards of Victorian propriety. Even so, the young men and the two communities seemed to have survived the experience and women's' barnstorming tours continued into the twentieth century when softball became the primary women's bat and ball game. But women's success in playing baseball against ongoing opposition reminds us that baseball was the National Pastime because it appealed to such a broad range of people, no matter how much others tried to limit who got on the field.

The Pall Mall Gazette (London, England) - May 23, 1893 - Bloomington is clearly Bloomfield

Keep Posting like this stuff

ReplyDeleteHappy Ramadan Quotes Wishes