Photo by Mark Granieri

Both matches were played by 1864 rules and the first contest was close until Flemington erupted for eight runs in the bottom of the eighth on the way to a 17-7 win. Ken "Tumbles" Mandel pitched for the Neshanock, but had an even more exceptional performance at the plate, walking each of the four times he came the striker's line. I'm not sure if "Tumbles" was put out on the bases, but if not this was his second unique clear score. Two years ago against these very same Athletics, he "earned" a clear score completely on Athletic fielding muffs. In the second game, the two clubs traded seven run innings early in the contest, but Flemington took an 18-11 lead going to the ninth behind the pitching of Brad "Brooklyn" Shaw. The Athletics staged a three run rally and had men on base, but the Neshanock held on for an 18-14 win.

Photo by Mark Granieri

Although I was present only in spirit, the Neshanock's trip to Philadelphia, along with my own "journey" through southern New Jersey newspapers led to some pondering on Philadelphia's influence on the development of base ball in New Jersey. As is well known in base ball history circles, beginning in the 1830's, young men in Philadelphia organized clubs to play a game called town ball by contemporaries, but today better referred to as Philadelphia town ball to distinguish it from other games with the same name. An excellent reconstruction of Philadelphia town ball by Richard Hershberger is available in Volume 1, Number 2 of Baseball: A Journal of the Early Game, but some of the major differences between it and the New York game include:

1. The bases consisted of five stakes in a circle about 30 feet in diameter with only about 19 feet between the bases.

2. For the side to be retired, all eleven batters had to be put out.

3. Runners could be put out by being hit with a thrown ball, an act known as "soaking or plugging."

4. After hitting the ball safely, runners could not stop at a base so that each at bat produced either an out or a run.

Reportedly the Athletic Club is going to recreate Philadelphia town ball at the Gettysburg vintage base ball festival the weekend of July 19-20th which should be well worth watching.

Olympic Club of Philadelphia Constitution

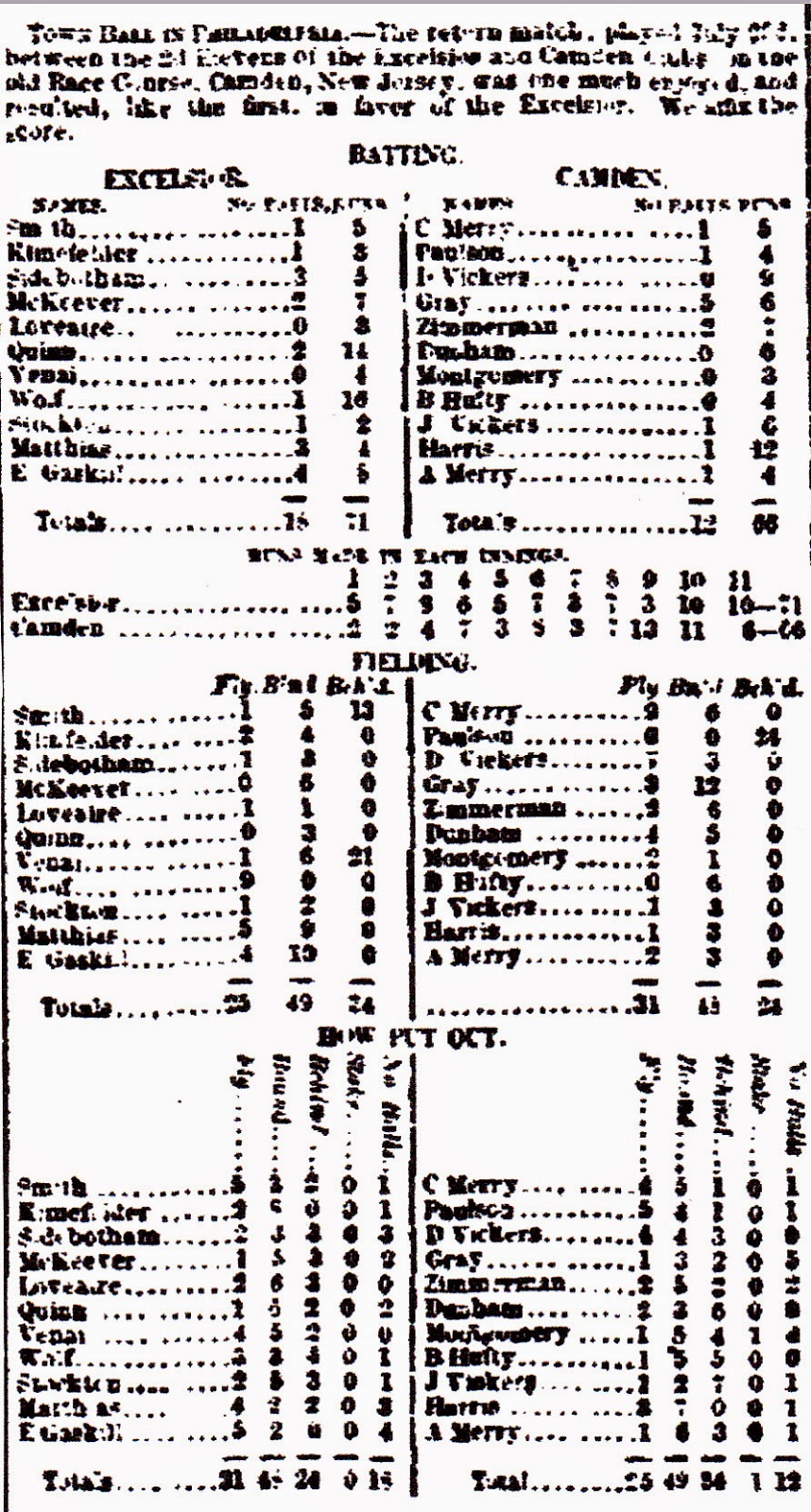

Best known of the city's town ball clubs was the Olympic Club which dates back to the early 1830's , making it more than ten years older than the better known Knickerbockers of New York City. Although these two pioneering clubs played a fundamentally different game, they had at least one thing in common, circumstances forced them to cross the river (Hudson or Delaware) and play in New Jersey (Hoboken or Camden). It took a while in both cases, but by the late 1850's, young men in New Jersey formed their own clubs to follow in the footsteps of their visitors from New York and Philadelphia. In the case of south Jersey this led to the formation of the Camden Club, thus far the only New Jersey team known to initially play town ball or more specifically Philadelphia town ball. But unlike the experience of the New York game in northern New Jersey, the expansion of Philadelphia town ball started and ended in Camden, Other than the Camden Club, reviews of newspapers in Camden, Gloucester, Ocean, Cape May, Cumberland and Burlington Counties produced not a single reference to town ball clubs through the entire antebellum period.

West Jerseyman - June 23, 1858

Why didn't Philadelphia town ball spread any further into New Jersey than Camden? And conversely why did the New York game reach as far as central New Jersey by 1860? In speculating about this or any issue regarding the spread of the early game, it is important to remember the limited number of ways one could experience, and thereby, become interested in, any new game. The practical possibilities were limited to witnessing a game in person, listening to an eyewitness who had seen or played in one or by reading about it in the newspaper, with the first two being the ones more likely to generate a lot of enthusiasm.

New York Clipper - August 11, 1860

Both seeing or hearing about base ball required a personal eyewitness so a key factor was the number of opportunities to see a game or at least talk to someone who either watched a match, or even better, played in one. To state the obvious, two things that increased or limited the seeing or listening possibilities were population and the transportation network. Both factors were important in northern New Jersey as clubs playing the New York game were formed not only in nearby and heavily populated Hudson and Essex Counties, but also in smaller Trenton, Elizabeth, Rahway, New Brunswick and even relatively rural Somerville.

Photo by Mark Granieri

As noted in prior posts, one common feature of these communities was a direct railroad link to Newark, Jersey City and ultimately New York. Not only did northern New Jersey have this railroad network, but by 1855, it had been in place for almost 15 years. According to John Cunningham in Railroads in New Jersey: The Formative Years, by 1850 this rail system carried significant commuter traffic to and from Manhattan as well as New Yorkers on excursions to contemporary recreational sites at places like Summit, Morristown and even Paterson. Both this relatively sophisticated railroad network and the volume of passenger traffic significantly increased the possibility of a base ball experience.

None of the railroads depicted on this map existed before the Civil War

South Jersey on the other hand had far less population and almost no rail network whatsoever. The nine southernmost counties had total 1860 population of about 227,000 compared to over 160,000 in Hudson and Essex counties alone. But even if the area had more people, convenient interaction with Philadelphia and Camden simply didn't exist. According to Cunningham there were no major railroads in south Jersey before 1860 and transportation to Philadelphia markets was limited to mule driven wagons and the Delaware River. From a recreational/vacation standpoint, Cape May was practically accessible only by boat and there was little in Atlantic City to attract Philadelphia vacationers to ride the first railroad to the future resort. Philadelphia town ball did receive some attention in the national sports weeklies including detailed game accounts in The New York Clipper, but other than very sporadic reports in the Camden newspapers, South Jersey papers took no notice of the game. Here again, south Jersey suffered in comparison with the rest of the state which had all of New Jersey's ten or so daily newspapers.

Photo by Mark Granieri

Regardless of whatever other factors may have worked against the expansion of Philadelphia town ball into south Jersey, there were simply too few potential players and a lack of convenient access to the game for those potential players. These factors most likely also explain why the New York game itself didn't make it south of Trenton until the war years when there was a different set of dynamics. The lack of development of any organized bat and ball games in the southern part of the state also suggests that northern New Jersey was uniquely positioned as a place where base ball could become well established once it moved beyond New York City and Brooklyn (a separate city until 1898). In addition to its proximity to those two major population centers, northern New Jersey had, for the time, a significant population base, a well developed transportation system and numerous daily newspapers. Without studying other communities near Manhattan and Brooklyn, it still seems reasonable to think it would be hard to find similar conditions any place close to the New York metropolitan area. Looking at how base ball expansion was different throughout the entire state demonstrates the importance of northern New Jersey's infrastructure to base ball's initial sustainability.

No comments:

Post a Comment