Photo by Mark Granieri

The latter half of the match was a back and forth affair with the Neshanock taking the lead and Elizabeth catching up. In the top of the ninth, Flemington held a one run lead and the Resolutes were down to their last out with no one base, but the Neshanock couldn't close it out and Elizabeth took a one run lead going to the bottom of the inning. Flemington had a runner on third with two out, but the match ended with Elizabeth prevailing by one tally. While it wasn't the cleanest played game on both sides, it was very competitive and a tough loss for the Neshanock.

Photo by Mark Granieri

Flemington had a balanced attack with Dan "Sledge" Hammer, Tom "Thumbs" Hoepfner, Scott "Snuffy" Hengst, Joe "Mick" Murray and Ken "Tumbles" Mandel each contributing two hits. Leading the attack, however was muffin Glen Modica, who in his first ever match, had three hits including a key bases loaded double in the Neshanock's eight run sixth. Well done sir! Let's hope the improved play in the second half of the match will be something to build on in the weeks ahead beginning next Saturday against the Athletic Club of Philadelphia in the City of Brotherly Love.

Photo by Mark Granieri

Recreating 19th century base ball in an enclosed ball park without an admission charge is more than a little ironic. Scheduling matches at enclosed facilities as well as building such facilities for base ball began primarily so that admission could be charged. The most noteworthy early instance of a match played on an enclosed ground with admission charge took place in the summer of 1858 in what has become known as the Fashion Course games. Named for a race track near today's Citi Field, the Fashion Course games were a best of three series between New York and Brooklyn "all star" teams. Large crowds, including a group from Jersey City, made their way to the site and paid 10 cents to enter the grounds with an additional 20 or 40 cents charge depending on whether your carriage was drawn by one or two horses.

Fashion Course Games - New York Clipper - July 24, 1858

Given the popularity of the series (won 2-1 by the New York side), it was only a question of time before someone tried a more permanent arrangement. Leading the way in 1862 was William Cammeyer, who opened his Union Grounds in the Williamsburgh section of Brooklyn to base ball matches. Three years later, Brooklyn got its second ball park, the Capitoline Grounds in Brownsville, and, according to William Ryczek in Baseball's First Inning, the two places became "the models for all others." One of the "others" hosted an 1864 New Jersey-Pennsylvania "all star" game as part of the U.S. Sanitary Commission Fair in Philadelphia. Located at Jefferson and 25th Street, near the Spring Garden Reservoir, the grounds were the new home of the Olympic Club, originally a Philadelphia town ball team older even than the Knickerbocker Club of New York. The gate receipts went for the benefit of the Sanitary Commission (a Union Soldier's Relief organization) which was probably the rationale for what appears to be base ball's first 25 cent admission fee, not including horses.

Brooklyn's Union Grounds

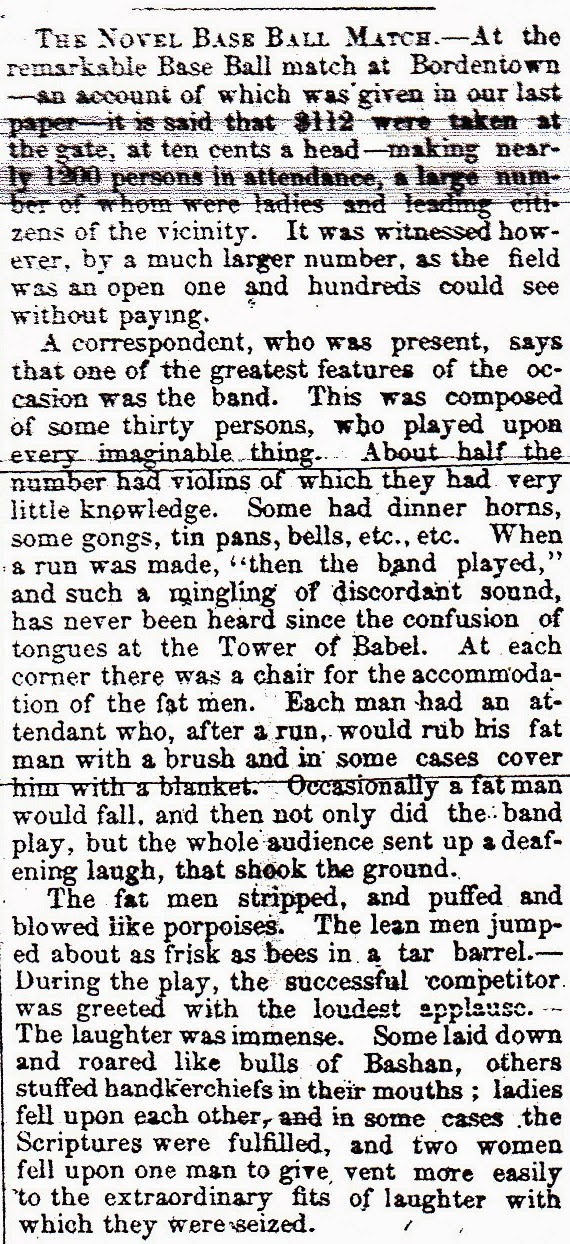

Although New Jersey's clubs played in games, like the 1864 Philadelphia match, where admission was charged, the first such game in New Jersey apparently wasn't played until 1866 and under more than unusual circumstances. According to the December 13, 1866 edition of a Mount Holly newspaper, a game was played in Bordentown a few days earlier between two teams "composed on the one side of some of the fattest men in the state, and on the other some of the leanest." Similar matches had been played in other parts of New Jersey, but in this case, a 10 cent admission fee was charged and reportedly $112 was collected, meaning over 1100 were present. The total crowd was actually described as being much larger as "the field was an open one and hundreds could see without paying." No explanation was provided as to what was done with the money or why so many people attended an outdoor event in December, a question perhaps better left unanswered.

New Jersey Mirror and Burlington County Advertiser - December 20, 1866

Admission fees did, however, become an issue for the state's leading clubs in the post war period. In August of 1867, the Newark Evening Courier lamented that unlike "all the other famous clubs," the Eureka lacked a permanent ground where they could "charge a small entrance fee" to "defray the expenses of the club." No further details were provided about the expenses, but other contemporary accounts strongly suggest the Eureka Club was paying at least some of its players. Supposedly the biggest obstacle to building an enclosed ground was the high cost of land in Newark and the paper urged concerned citizens to support the club financially because the Eureka were "a big advertising card for us." Unfortunately this and any other such efforts were fruitless and the Eureka Club played only one more full season.

Edward "The Only" Nolan

A year later in 1868, the Olympic Club of Paterson, honored with a visit from the renown Brooklyn Atlantics, adopted the Fashion Course model, by using the Paterson racetrack to host the match. Reportedly there was "quite a large crowd," in spite of a 25 cent admission charge, but unfortunately a large number of people got in without paying and the two clubs "lost considerable money by the blunder." Whether financial issues were a contributing factor isn't clear, but the Olympics were largely inactive after 1868 until the club was reborn in the 1870's when it produced four future major leaguers including one Hall of Fame player, Michael "King" Kelly and one Hall of Fame nickname, Edward "The Only" Nolan.

Photo by Mark Granieri

By 1870 admission fees were becoming fairly standard at a wide range of New Jersey locations including Jersey City, Somerville and Trenton. In Jersey City, the Champion Club solved the lack of an enclosed ground by building a "tier of seats," for which they charged admission, women were admitted to the seats at no charge. Initially admission to this version of a 19th century "luxury box" cost 10 cents, but went up to 25 cents for a match with the Star Club of Brooklyn which reportedly attracted "several thousand" even at the higher price. While the quality of play probably wasn't as high as in Jersey City, the Somerset Unionist informed prospective spectators to a "Waxer" Club of Somerville match that admission for the contest against the "Centrals" of Plainfield would cost adults 25 cents and children a dime.

Children's Soldier's Home, Trenton - 1873

With the exception of the match at the Paterson racetrack, none of these contests were played on an enclosed ground. Surprisingly, it seems New Jersey's first enclosed base ball field was built not in one of the state's larger cities, but in the relatively less populous state capital at Trenton. In June of 1870, the Daily True American reported construction of a new base ball and cricket grounds that was "completely fenced" near the new Soldier's Children's Home at the intersection of Hamilton and Chestnut Streets. Built to house orphans left behind by the state's Civil War veterans, the property ultimately became the first New Jersey Institute for the Deaf. An admission fee of "a quarter of a dollar" was charged for a June 24th match with the well known Athletic Club of Philadelphia and a crowd estimated at 700 paid to see the Trenton Club decisively defeated 48-11. Apparently not in the least bit intimidated, the Trenton Club again stepped up on class in September and were shut out 19-0 by the New York Mutuals. Regardless of the result, it was clear that enclosed ball parks and admission fees were here to stay.

Photo by Mark Granieri

No comments:

Post a Comment