The first edition of the Evening Journal (today's Jersey Journal) May 2,1867

Recently, however, the veil lifted ever so slightly in a series of late 1860's newspaper references to black base ball clubs in Jersey City which facilitated a closer look at this hidden aspect of the state's base ball history. The reports appeared in only one of the city's three daily newspapers, the Evening Journal and initially focused more on equal rights than base ball. Founded in 1867, the paper, which continues today as the Jersey Journal, used its first editorial to proclaim its commitment to the "equality of all before the law." As a result it was only logical for the paper to take exception to the National Association of Base Ball Players' refusal to admit black clubs. The Journal briefly mentioned the issue in a December 13, 1867 reference to the Oneida Base Ball Club, a black Jersey City club, not previously mentioned in Jersey City papers. A few days later, the paper excoriated the National Association for a policy that while probably legal, was incompatible with any sense of fairness.

Evening Journal -December 13, 1867

While the paper's position had no impact at the national level, it led to more publicity for the Oneida Club beginning with an account of a July 1868 "scrub game" against the Oriental Club of neighboring Bergen, another black club. In those strictly segregated times, finding other black clubs to play against was only one of unique challenges facing early black base ball teams. Even more challenging was the problem of filling a roster from the extremely limited pool of potential players. Statewide in 1860, New Jersey had a black population of over 25,000, out of a total state population of about 672,000, which according to historian Bill Gillette was "the highest proportion of blacks in any free state." However contrary to what we might expect, the state's black population wasn't concentrated in large urban areas. Newark had only about 1300 black residents in 1860 (total city population of 72,000), but far more than Jersey City with just 335 black residents (total city population of 29,000) only 141 of whom were male.

Area in red represents an 1867 black community in Jersey City bounded by 6th Street on the north, Monmouth Street on the east and Newark Avenue on the south and west

While there may have been 141 black males in Jersey City, the number of potential base ball players was obviously lower because of those who were either too young or too old. Almost all of the men lived in the city's 3rd and 4th wards facilitating a closer look at this group. In order to estimate the potential number of players for an 1867-68 club from the 1860 census every black resident under 10 or over 35 was eliminated which left 80 possibilities. While this does not take into account population changes between 1860 and 1867, it demonstrates the limited numbers involved. Further light on the subject is provided by Gopsill's 1867 directory for Jersey City and Hoboken which, while not a census, appears to list information about heads of households including race, occupation and address. Going through this source revealed an even lower number of 45 black males, about half of whom lived on south 6th street in the city's 3rd ward. Another 14 lived on nearby Newark Avenue and Monmouth Streets suggesting a small concentration of black residents in the area outlined in red on the above map.

Within walking distance of this neighborhood were two of Jersey City's leading 19th century base ball grounds at Hamilton Park and at the head of Erie Street so this black community didn't lack for opportunities to see games in person. Easy access to playing fields apparently continues in the area as the modern map shows three base ball fields close by. While the directory data certainly doesn't identify any of the residents of this little community as members of the Oneida Club, it is reasonable to believe the members of the Oneida and any other black clubs worked at similar occupations. As might be expected most held jobs at the lower end of the economic spectrum although there was one jeweler. Much more common were laborers, boatmen, coachmen, porters and waiters which is different from the city's white clubs who were primarily skilled workers or worked at some form of a white collar job. In addition to not paying well, these jobs would seem to have offered limited flexibility in working hours thereby complicating the scheduling of matches and practices.

While nothing thus far has identified any of Jersey City's black base ball players, the July 10, 1868 Journal article about the the previously mentioned "scrub match" names two players, even providing first names or initials for Ben Cisco and P.P. Lewis. Given the extremely limited number of black males in Jersey City at the time, it isn't difficult (or surprising) to find both men as residents of the 6th street community with Cisco, a coachman living at 327 6th street and Lewis, full name, Peter P. Lewis, a barber living nearby at 360. Little additional information has been found about Cisco, but Lewis was without question a prominent member and leader of the city's small black community. Ads for his hair dressing saloon (special attention paid to children) appeared regularly in the Evening Journal, suggesting the financial wherewithal to pay for advertising in a paper supportive of the black community. Lewis' customer base had to be predominantly white as he would have gone out of business pretty quickly if his clientele was limited to the black community, even if all of the 335 listed on the 1860 census were his customers. It's certainly not unreasonable to believe some of the growing number of Jersey City white base ball players were among his customers, giving Lewis the ability to learn about base ball both by watching it and hearing about it. During the 1870's, Lewis was the president of the First District (colored) Republican Club, grand warden of a lodge and a leader of the Union Club (colored)

Evening Journal - July 10, 1868

Within walking distance of this neighborhood were two of Jersey City's leading 19th century base ball grounds at Hamilton Park and at the head of Erie Street so this black community didn't lack for opportunities to see games in person. Easy access to playing fields apparently continues in the area as the modern map shows three base ball fields close by. While the directory data certainly doesn't identify any of the residents of this little community as members of the Oneida Club, it is reasonable to believe the members of the Oneida and any other black clubs worked at similar occupations. As might be expected most held jobs at the lower end of the economic spectrum although there was one jeweler. Much more common were laborers, boatmen, coachmen, porters and waiters which is different from the city's white clubs who were primarily skilled workers or worked at some form of a white collar job. In addition to not paying well, these jobs would seem to have offered limited flexibility in working hours thereby complicating the scheduling of matches and practices.

While nothing thus far has identified any of Jersey City's black base ball players, the July 10, 1868 Journal article about the the previously mentioned "scrub match" names two players, even providing first names or initials for Ben Cisco and P.P. Lewis. Given the extremely limited number of black males in Jersey City at the time, it isn't difficult (or surprising) to find both men as residents of the 6th street community with Cisco, a coachman living at 327 6th street and Lewis, full name, Peter P. Lewis, a barber living nearby at 360. Little additional information has been found about Cisco, but Lewis was without question a prominent member and leader of the city's small black community. Ads for his hair dressing saloon (special attention paid to children) appeared regularly in the Evening Journal, suggesting the financial wherewithal to pay for advertising in a paper supportive of the black community. Lewis' customer base had to be predominantly white as he would have gone out of business pretty quickly if his clientele was limited to the black community, even if all of the 335 listed on the 1860 census were his customers. It's certainly not unreasonable to believe some of the growing number of Jersey City white base ball players were among his customers, giving Lewis the ability to learn about base ball both by watching it and hearing about it. During the 1870's, Lewis was the president of the First District (colored) Republican Club, grand warden of a lodge and a leader of the Union Club (colored)

Evening Journal June 11, 1868

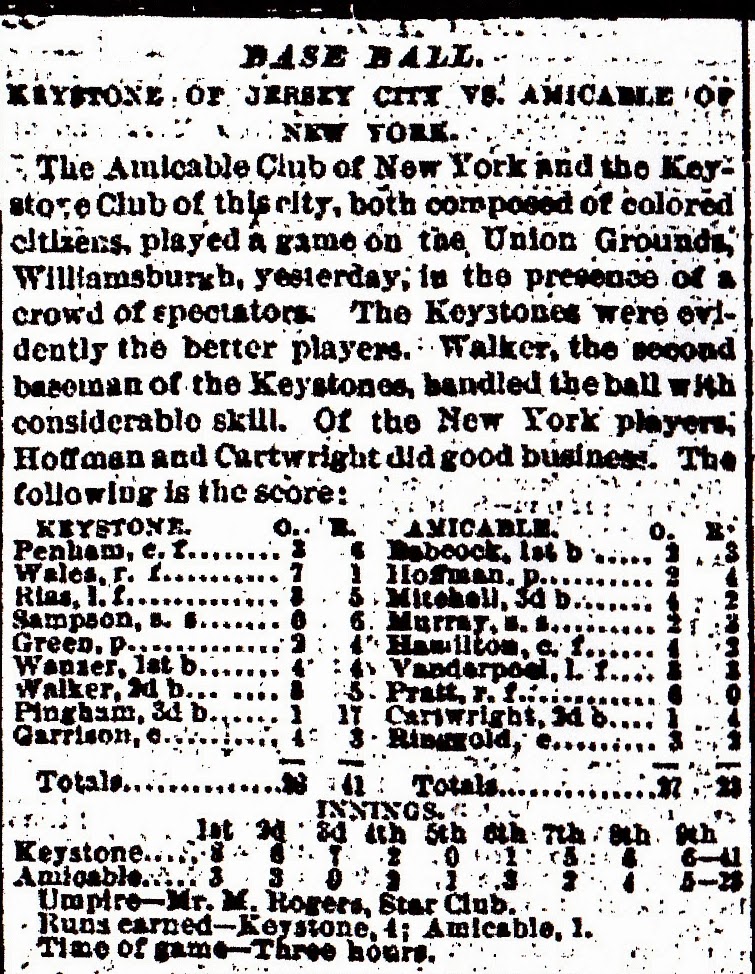

How involved Lewis was in base ball beyond playing for the Oneida Club is uncertain, but base ball was definitely taking root in Jersey City's black community. In June of 1868 the Journal announced that George Gale, Isaac Walker and Robert McClean had been elected officers of a second black club, the Liberty Club. The three ranged in age from 12 to 15 so this was clearly a junior club, perhaps one of the state's first junior black clubs. Nothing further has been found about the Liberty, but in 1871, George Gale was elected Treasurer of the Keystone Club which later that year not only had a game account published in the Journal, but was also the lead base ball story complete with box score. In spite of all the things working against them, blacks had established a base ball presence in New Jersey's second largest city.

Evening Journal - September 30, 1871

No comments:

Post a Comment