Area in red is a modern view of the grounds "at the head of Erie Street." Erie Street is on the left, Grove Street on the right and Jersey Avenue at the bottom.

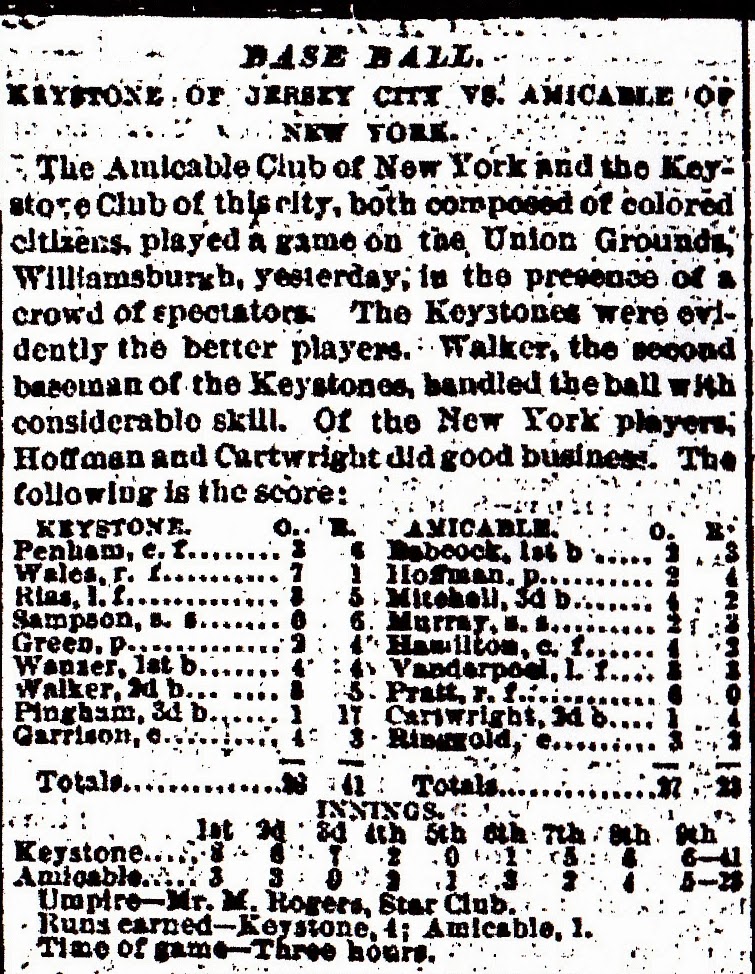

The frequency of matches along with the downtown location meant there was never a shortage of bystanders and hangers-on. Such was apparently the case on August 31, 1870 when some of the Champion Club plus two members of the Aetna Club arrived at the grounds to watch a match between two other clubs. For some reason, however, there was no game going on and the vacant field on a warm summer day was too big a temptation to pass up. Accordingly Myles McCartin and Hudson Clarke of the Aetnas, Ed Beakes of the Champions along with some "heelers of the Champions" including President Joseph Weltch, Edward Sturges, Samuel Stilsing and Sidney Barr decided to have some fun by playing a team "conscripted" from the onlookers "without respect to age or color" (emphasis mine). The result claimed the Evening Journal was a "game extraordinary" as the Champion/Aetna group took on "a club of mixed races." Most likely the black members (who as usual were not identified) were residents of the small black community located nearby on 6th Street. The match lasted only an inning or so and was reportedly "muffin all around" so it's unlikely the black members came from one of the city's early black clubs.

Leon Abbett - forceful and articulate Democratic political leader from Jersey City, according to one historian - "In short, he was a racist."

This "match" is the earliest documented instance of blacks and whites in New Jersey playing base ball together. Given its informal, unplanned nature, the isolated event would, in most years, have gone unnoticed and unreported. 1870, however, was not a typical year as New Jersey and the nation were about to enter the first election campaign in the wake of the ratification of the XVth Amendment to the Constitution guaranteeing to blacks (at least theoretically) the right to vote. Passed by Congress on February 26, 1869 the XVth amendment was considered for ratification by the states during the early part of 1870. Perhaps surprisingly to us today, like the other two reconstruction amendments, the XVth wasn't popular with the Democratic party in New Jersey and elsewhere. The political philosophy of 19th century Democrats was very different from today with a strong emphasis on states rights and a limited role for the Federal government, both reasonable positions of responsible people. Unfortunately, these views were accompanied by blatant racial prejudice against blacks and fierce opposition to attempts to secure their rights, including the vote.

Evening Journal - February 3, 1870

Equally unfortunately, for anyone favoring the XVth amendment, including New Jersey's black population, the state's decision on the amendment was in the unsympathetic hands of the Democratically controlled state legislature. Secure in their numbers, Democratic leaders like Leon Abbett of Jersey City didn't hold back on their rhetoric, even questioning the role of "colored troops" in the recent war claiming "they [black troops] did not show bravery in a single instance." Justifiably outraged, Zebina Pangborn, editor of the Evening Journal, asked rhetorically if Abbett and other Democrats had ever heard of battles like "Port Hudson, Fort Wagner, Olustee or Petersburg." Probably as he anticipated, Pangborn's pleas yielded little as a Democratic resolution rejecting the proposed amendment passed on a strict party vote as according to the Journal, New Jersey Democrats were once again "making a record of which their children will be ashamed." Fortunately the fate of the amendment wasn't controlled by one recalcitrant legislature and the XVth amendment became the law of the land, including New Jersey, in February of 1870.

Zebina Pangborn - Editor of the Evening Journal

As a result the "integrated" base ball event took place just as the state was gearing up for the first election with an enfranchised black population. Even though Jersey City had a minuscule black population which was far too small to swing an election, the American Standard, the city's Democratic newspaper, was outraged by the inter-racial activity. Claiming that "the result of the Fifteenth Amendment was never more practically illustrated," the paper lamented the behavior of some of the city's "brightest," "respectable," and "it was always supposed, thoroughly Democratic young men." The supposition was, in fact, inaccurate as at least three participants were active in the Republican party. Ironically, Sid Barr, who the paper singled out for "hugging and embracing his 'colored brethren" with the result of "wiping out (in Jersey City at least) of the dividing line between the races," was actually a Democrat. All in all, the paper found the event an "unlooked for degradation of the Champs [the Champion Club]" that "can only be pardoned by a long season of repentance."

Evening Journal - November 9, 1870 celebrating the election results

If the American Standard was worried about the impending election campaign, the paper had good reason as November saw the Republican party capture both houses of the stage legislature (and with it the power to elect the state's U.S. Senators) and the Congressional delegation. Perhaps seeing the handwriting on the wall, Abbett declined to run, citing other responsibilities. The Jersey City man was far from finished in politics, however, as he was elected governor twice, serving from 1884 to 1887 and then from 1890 to 1893. For the moment, however, Panborn and Evening Journal enjoyed the results which if "wisely used will make New Jersey permanently a Republican state." Panborn also continued to advocate for equality on the base ball field, again excoriating the National Association of Base Ball Players for its exclusion of black clubs. It would take many years to reach any level of racial equality both in base ball and daily life, but it's nice to know that there were men like Panborn and those early New Jersey ball players who did the right thing when it was far from an easy and popular choice.